Timor-Leste and Australia

Bugs in the pipeline

Timorese leaders push for a better deal from their offshore gas fields

Whatever the truth, leaders in Timor-Leste feel Australia took advantage of them. In 2004 the tiny nation was still recovering from the devastation that followed its vote for independence from Indonesia in a UN-organised referendum in 1999. The Indonesian army and supporting militias had sought revenge in a rampage of killing and destruction.

Ever since, Timor-Leste’s hopes of prosperity have rested on offshore oil and gas reserves. But most are located in the Timor Gap, under waters also claimed by Australia. Cash-strapped and desperate for revenue to start flowing, leaders saw no option but to agree to treaties with Australia that many in Timor-Leste see as unfair.

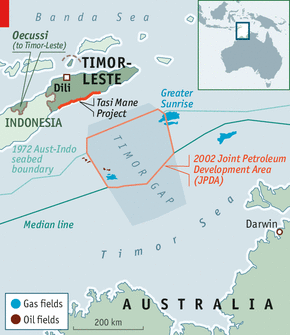

In all, three linked treaties covering the Timor Gap were signed, but the maritime boundaries were never agreed upon. The first, the Timor Sea Treaty, signed in 2002, gives Timor-Leste 90% of the revenue from a Joint Petroleum Development Area (JPDA). This meant that revenues could start flowing.

The JPDA was a compromise between Australia’s insistence the maritime boundary be the deepest point as agreed with Indonesia in 1972, and Timor-Leste’s hope to use the “median line”, halfway across the sea. Only 20% of one of the largest fields, Greater Sunrise, is within the JPDA.

Then another treaty was signed in 2006, after two years of tortuous negotiations, during which the alleged spying took place. This one gives each country an equal share of revenue from Greater Sunrise on condition that they waive their rights to assert sovereignty, or pursue any legal claim over the border, for 50 years.

It is this treaty that rankles with the Timorese. If the median line were the border, Greater Sunrise and many other fields would fall in Timorese waters. Mr Pires says that the uncertainty about the maritime boundary makes it hard to plan for the long term or to attract investment.

Despite its growing oil wealth (its petroleum fund already contains $13 billion) Timor-Leste remains one of Asia’s poorest countries. It is pinning its hopes on the Tasi Mane project, an ambitious plan to build a gas plant to process gas from Greater Sunrise, and a refinery and associated petrochemical industry. That is a gamble as long as the sovereignty issue is unresolved and an impasse persists over the route of a gas pipeline from Greater Sunrise. Timor-Leste wants a pipeline to Tasi Mane to bring jobs and income. Australia wants a pipeline to Darwin.

The bugging allegation and arbitration proceedings seem intended to force Australia to the negotiating table. Leaders in Timor-Leste hope to break the logjam and perhaps to win a better deal.

Timor-Leste and AustraliaBugs in the pipelineTimorese leaders push for a better deal from their offshore gas fieldsJun 8th 2013 | SINGAPORE | From the print editionTimekeeperTHE future finances of the young, poor nation of Timor-Leste, formerly East Timor, have become embroiled in allegations of skulduggery by Australia nearly a decade ago. Timor-Leste has taken its big, wealthy neighbour to arbitration over a 2006 agreement on the exploitation of oil and gas in the sea between them.

Speaking on a visit to Singapore this week, Timor-Leste’s oil minister, Alfredo Pires, claimed to have “irrefutable proof” that, during negotiations in 2004, Australia’s secret services had illegally obtained information.

His lawyer claims the Timorese prime minister’s offices were bugged.Whatever the truth, leaders in Timor-Leste feel Australia took advantage of them. In 2004 the tiny nation was still recovering from the devastation that followed its vote for independence from Indonesia in a UN-organised referendum in 1999. The Indonesian army and supporting militias had sought revenge in a rampage of killing and destruction.In this sectionLong, hot summer Bugs in the pipelineA successful show begins to pallLights, camera, election Mr Joko goes to Jakarta ReprintsRelated topicsPoliticsAustralian politicsInternational relationsAsia-Pacific politicsPolitical policyEver since, Timor-Leste’s hopes of prosperity have rested on offshore oil and gas reserves.

But most are located in the Timor Gap, under waters also claimed by Australia. Cash-strapped and desperate for revenue to start flowing, leaders saw no option but to agree to treaties with Australia that many in Timor-Leste see as unfair.In all, three linked treaties covering the Timor Gap were signed, but the maritime boundaries were never agreed upon.

The first, the Timor Sea Treaty, signed in 2002, gives Timor-Leste 90% of the revenue from a Joint Petroleum Development Area (JPDA). This meant that revenues could start flowing.The JPDA was a compromise between Australia’s insistence the maritime boundary be the deepest point as agreed with Indonesia in 1972, and Timor-Leste’s hope to use the “median line”, halfway across the sea. Only 20% of one of the largest fields, Greater Sunrise, is within the JPDA.Then another treaty was signed in 2006, after two years of tortuous negotiations, during which the alleged spying took place.

This one gives each country an equal share of revenue from Greater Sunrise on condition that they waive their rights to assert sovereignty, or pursue any legal claim over the border, for 50 years.It is this treaty that rankles with the Timorese. If the median line were the border, Greater Sunrise and many other fields would fall in Timorese waters. Mr Pires says that the uncertainty about the maritime boundary makes it hard to plan for the long term or to attract investment.Despite its growing oil wealth (its petroleum fund already contains $13 billion) Timor-Leste remains one of Asia’s poorest countries.

It is pinning its hopes on the Tasi Mane project, an ambitious plan to build a gas plant to process gas from Greater Sunrise, and a refinery and associated petrochemical industry. That is a gamble as long as the sovereignty issue is unresolved and an impasse persists over the route of a gas pipeline from Greater Sunrise. Timor-Leste wants a pipeline to Tasi Mane to bring jobs and income. Australia wants a pipeline to Darwin.The bugging allegation and arbitration proceedings seem intended to force Australia to the negotiating table. Leaders in Timor-Leste hope to break the logjam and perhaps to win a better deal.From the print edition: Asia

Timor-Leste and AustraliaBugs in the pipelineTimorese leaders push for a better deal from their offshore gas fieldsJun 8th 2013 | SINGAPORE | From the print editionTimekeeperTHE future finances of the young, poor nation of Timor-Leste, formerly East Timor, have become embroiled in allegations of skulduggery by Australia nearly a decade ago. Timor-Leste has taken its big, wealthy neighbour to arbitration over a 2006 agreement on the exploitation of oil and gas in the sea between them.

Speaking on a visit to Singapore this week, Timor-Leste’s oil minister, Alfredo Pires, claimed to have “irrefutable proof” that, during negotiations in 2004, Australia’s secret services had illegally obtained information. His lawyer claims the Timorese prime minister’s offices were bugged.Whatever the truth, leaders in Timor-Leste feel Australia took advantage of them. In 2004 the tiny nation was still recovering from the devastation that followed its vote for independence from Indonesia in a UN-organised referendum in 1999.

The Indonesian army and supporting militias had sought revenge in a rampage of killing and destruction.In this sectionLong, hot summerBugs in the pipelineA successful show begins to pallLights, camera, electionMr Joko goes to JakartaReprintsRelated topicsPoliticsAustralian politicsInternational relationsAsia-Pacific politicsPolitical policyEver since, Timor-Leste’s hopes of prosperity have rested on offshore oil and gas reserves. But most are located in the Timor Gap, under waters also claimed by Australia.

Cash-strapped and desperate for revenue to start flowing, leaders saw no option but to agree to treaties with Australia that many in Timor-Leste see as unfair.In all, three linked treaties covering the Timor Gap were signed, but the maritime boundaries were never agreed upon.

The first, the Timor Sea Treaty, signed in 2002, gives Timor-Leste 90% of the revenue from a Joint Petroleum Development Area (JPDA). This meant that revenues could start flowing.The JPDA was a compromise between Australia’s insistence the maritime boundary be the deepest point as agreed with Indonesia in 1972, and Timor-Leste’s hope to use the “median line”, halfway across the sea. Only 20% of one of the largest fields, Greater Sunrise, is within the JPDA.Then another treaty was signed in 2006, after two years of tortuous negotiations, during which the alleged spying took place.

This one gives each country an equal share of revenue from Greater Sunrise on condition that they waive their rights to assert sovereignty, or pursue any legal claim over the border, for 50 years.It is this treaty that rankles with the Timorese. If the median line were the border, Greater Sunrise and many other fields would fall in Timorese waters. Mr Pires says that the uncertainty about the maritime boundary makes it hard to plan for the long term or to attract investment.Despite its growing oil wealth (its petroleum fund already contains $13 billion) Timor-Leste remains one of Asia’s poorest countries.

It is pinning its hopes on the Tasi Mane project, an ambitious plan to build a gas plant to process gas from Greater Sunrise, and a refinery and associated petrochemical industry. That is a gamble as long as the sovereignty issue is unresolved and an impasse persists over the route of a gas pipeline from Greater Sunrise. Timor-Leste wants a pipeline to Tasi Mane to bring jobs and income. Australia wants a pipeline to Darwin.The bugging allegation and arbitration proceedings seem intended to force Australia to the negotiating table. Leaders in Timor-Leste hope to break the logjam and perhaps to win a better deal.From the print edition: Asia

Penulis : Drs.Simon Arnold Julian Jacob

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar

ORANMG PINTAR UNTUK TAMBAH PENGETAHUAN PASTI BACA BLOG 'ROTE PINTAR'. TERNYATA 15 NEGARA ASING JUGA SENANG MEMBACA BLOG 'ROTE PINTAR' TERIMA KASIG KEPADA SEMUA PEMBACA BLOG 'ROTE PINTAR' DIMANA SAJA, KAPAN SAJA DAN OLEG SIAPA SAJA. NAMUN SAYA MOHON MAAF KARENA DALAM BEBERAPA HALAMAN DARI TIAP JUDUL TERDAPAT SAMBUNGAN KATA YANG KURANG SEMPURNA PADA SISI PALING KANAN DARI SETIAP HALAM TIDAK BERSAMBUNG BAIK SUKU KATANYA, OLEH KARENA ADA TERDAPAT EROR DI KOMPUTER SAAT MEMASUKKAN DATANYA KE BLOG SEHINGGA SEDIKIT TERGANGGU, DAN SAYA SENDIRI BELUM BISA MENGATASI EROR TERSEBUT, SEHINGGA PARA PEMBACA HARAP MAKLUM, NAMUN DIHARAPKAN BISA DAPAT MEMAHAMI PENGERTIANNYA SECARA UTUH. SEKALI LAGI MOHON MAAF DAN TERIMA KASIH BUAT SEMUA PEMBACA BLOG ROTE PINTAR, KIRANYA DATA-DATA BARU TERUS MENAMBAH ISI BLOG ROTE PINTAR SELANJUTNYA. DARI SAYA : Drs.Simon Arnold Julian Jacob-- Alamat : Jln.Jambon I/414J- Rt.10 - Rw.03 - KRICAK - JATIMULYO - JOGJAKARTA--INDONESIA-- HP.082135680644 - Email : saj_jacob1940@yahoo.co.id.com BLOG ROTE PINTAR : sajjacob.blogspot.com TERIMA KASIH BUAT SEMUA.